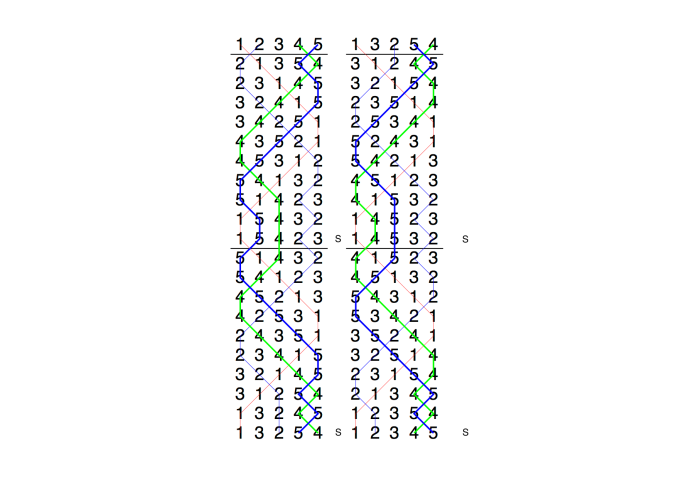

If you can treble to Grandsire Doubles, sooner or later you’ll be asked to treble to Plain Bob Doubles, and you might then want to ring it ‘inside’. Let’s find out what it is.

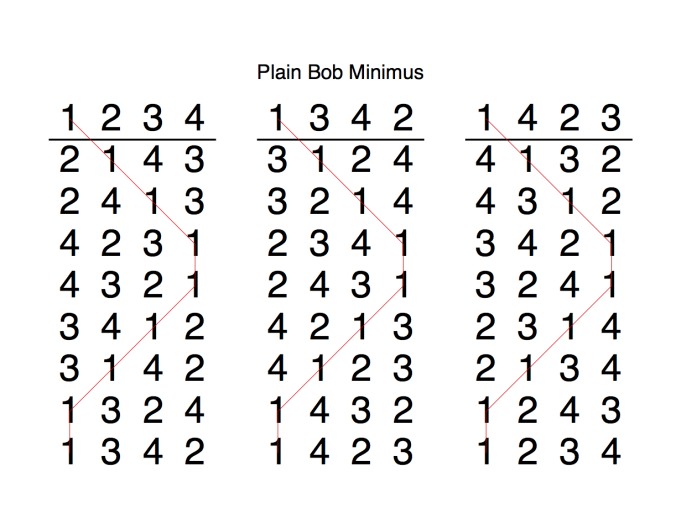

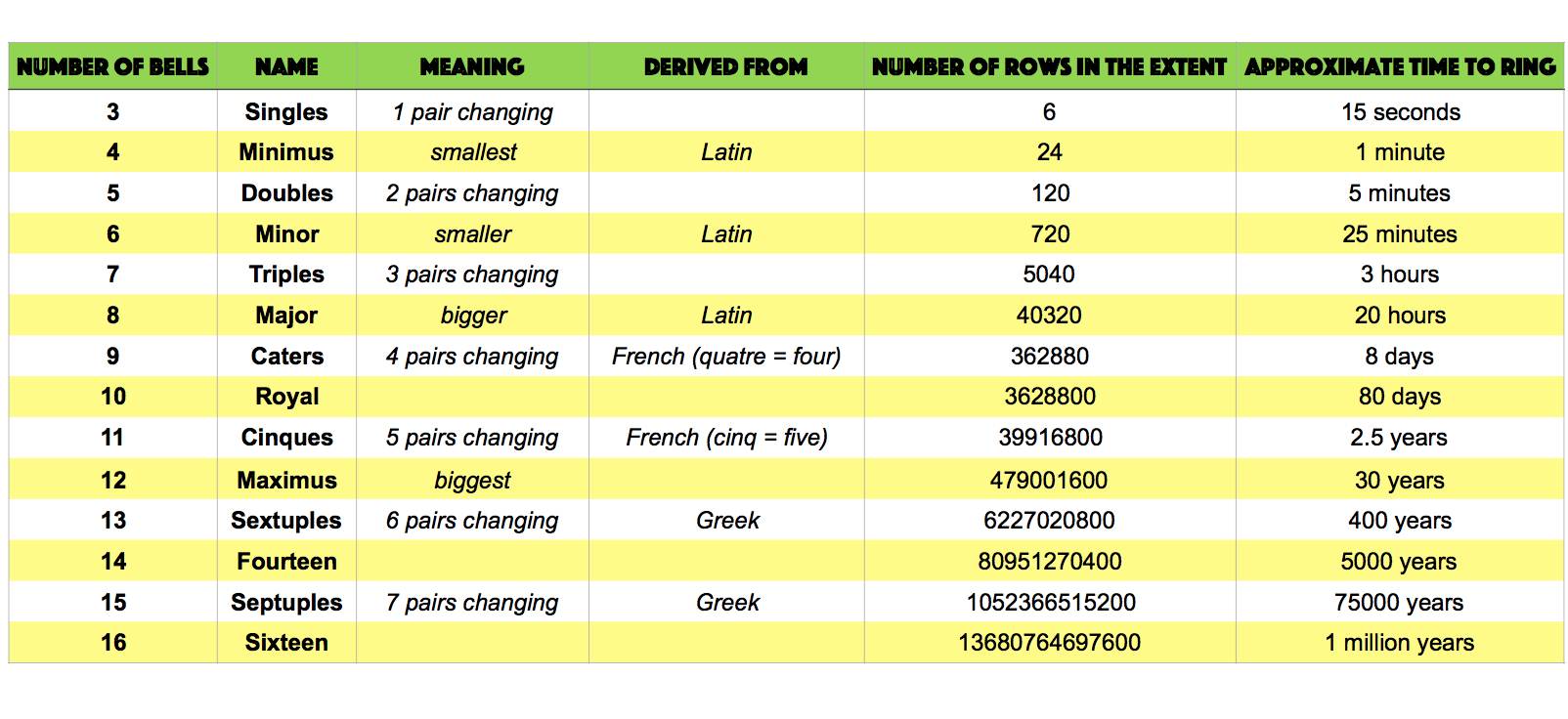

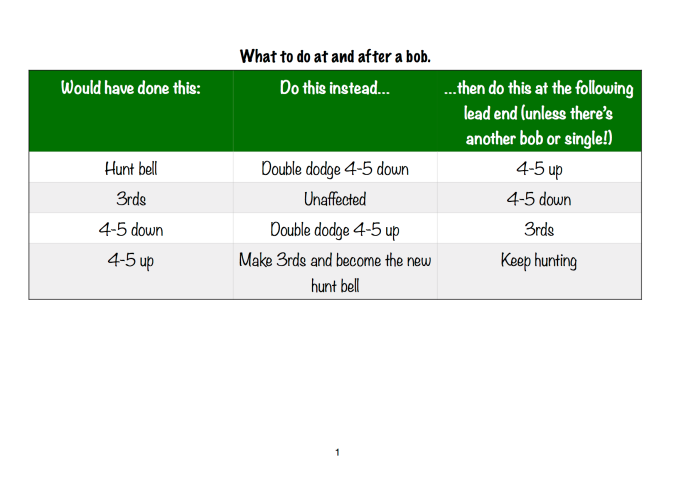

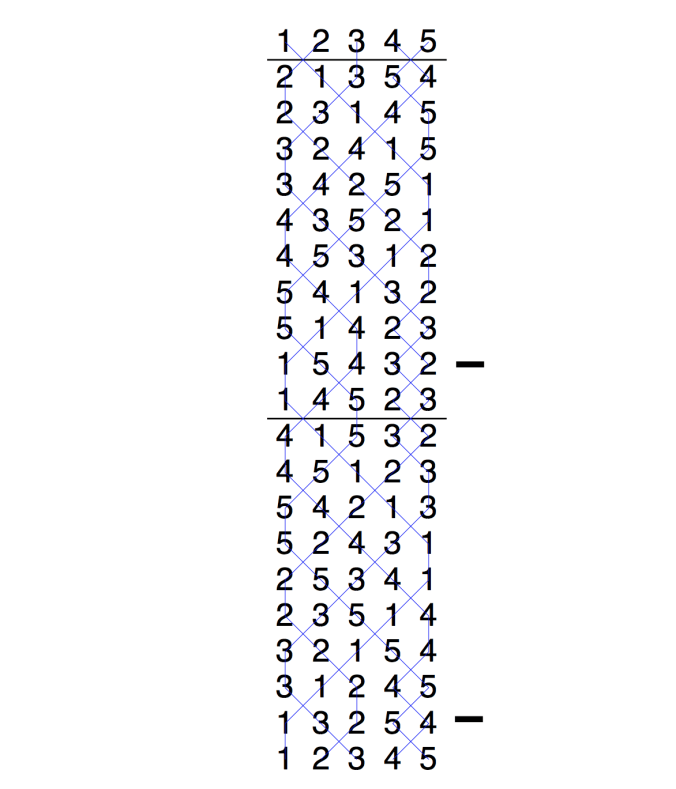

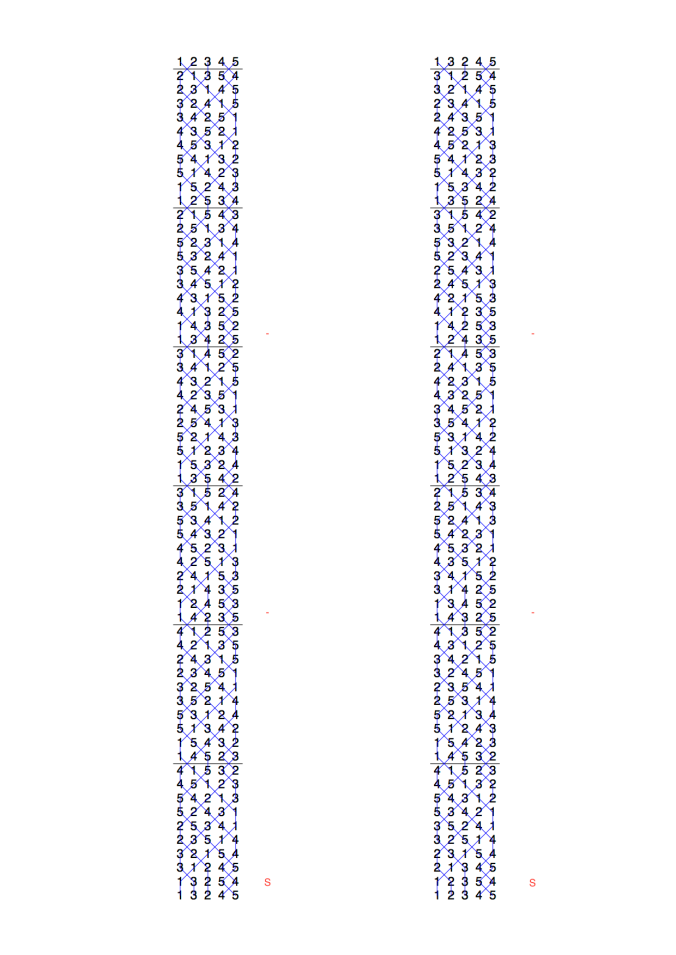

Like Grandsire, Plain Bob is just Plain Hunt with the occasional tweak. In Grandsire, the tweak happens at the start of the lead; in Plain Bob, it happens at the end. Plain Bob Doubles starts with a full lead of Plain Hunt then, at the very last change, to stop it coming back into rounds, a bell makes 2nds over the treble, the bells in 3-4 dodge, and the bell in 5ths stays put. This brings up the row 13524. If you do this three more times, the bells run round, giving a plain course of 40 rows, each 10 rows long. Here’s a diagram:

There is a very significant difference between Grandsire and Plain Bob:

- In a plain course of Grandsire Doubles (as you already know), all the rows are in-course. You need singles to get the out-of-course rows.

- In a plain course of Plain Bob Doubles, half the rows are in-course (the first and third leads) and half are out-of-course (the second and fourth leads). This is because every time the treble leads, three bells (including the treble) lie still; just one pair swaps (the bells dodging in 3-4), and it’s this single change which flips the rows from in-course to out-of-course, or vice-versa.

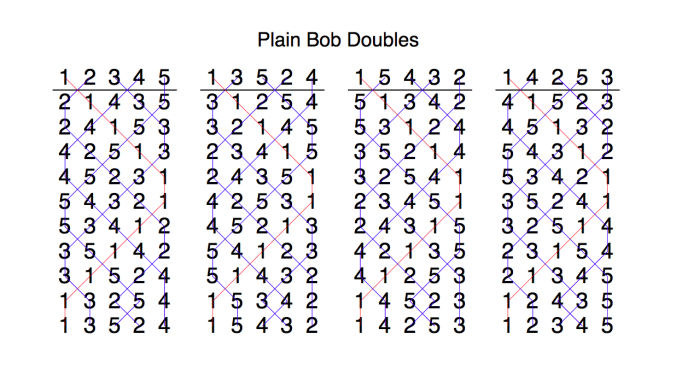

You might therefore guess that the extent of Plain Bob Doubles doesn’t need any singles, and you’d be right: it only needs bobs. In fact, producing a 120 of Bob Doubles is very straightforward. At the end of the course, instead of a bell making 2nds, a bell makes 4ths, bringing up the row 14235. The whole thing is repeated twice, running round after 120 rows.

Plain Bob is the simplest of the huge number of methods which have a 2nds place lead end and a 4ths place bob. If you’ve trebled to Bob Doubles, you’ve probably noticed the bell making 2nds over you every time you lead, except when a bob was called.

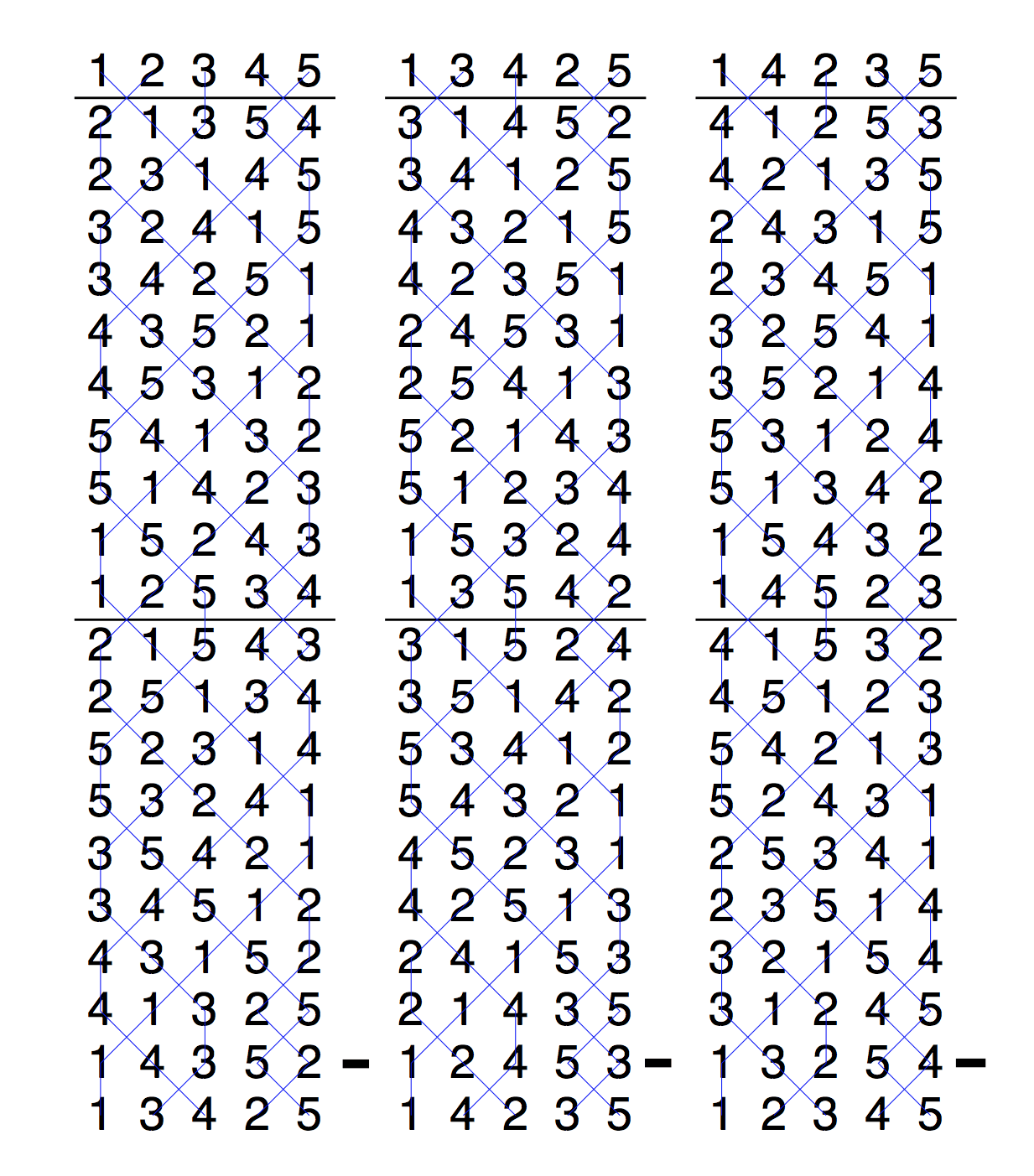

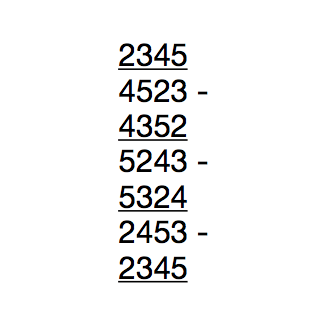

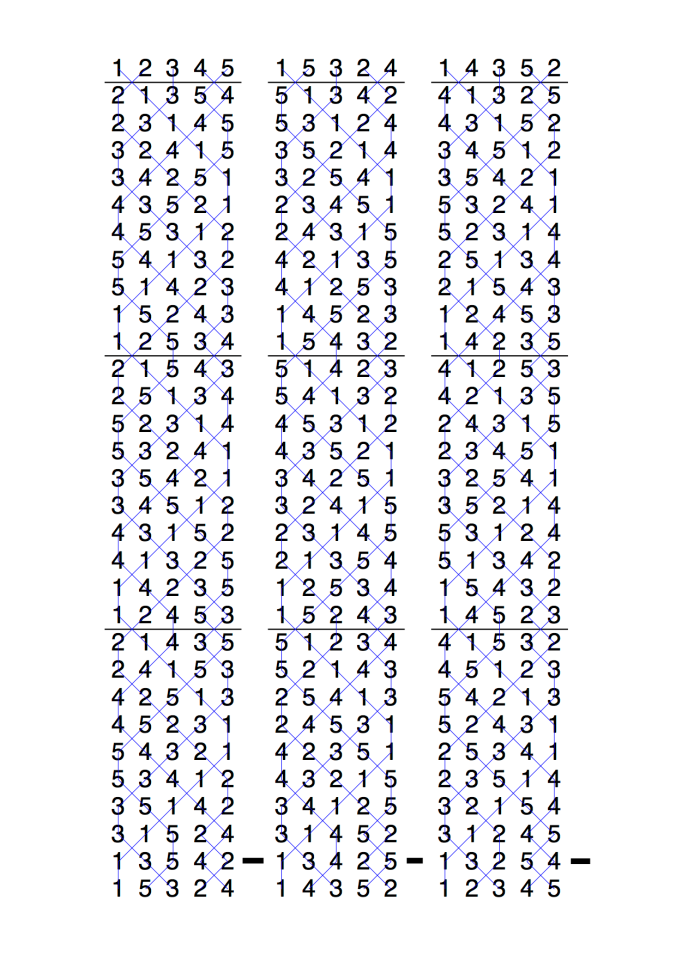

Here’s the extent described above:

Because the extent of Bob Doubles is a round block, the three bobs can be called at any three lead ends 40 changes (4 leads) apart. The extent shown above has the 5th as observation, and has bobs at the 4th, 8th and 12th lead ends. The 5th simply rings three plain courses and is unaffected by the bobs. Any of the other three bells may be called to be observation bell. You simply call a bob each time your choice of observation bell is at the back as the treble is leading. For instance, to call the 2nd observation you would need bobs at the 2nd, 6th and 10th lead ends. A useful exercise would be to write out an extent of Bob Doubles with either 2, 3 or 4 as the observation bell.

We’ll think about how to ring Bob Doubles next time.

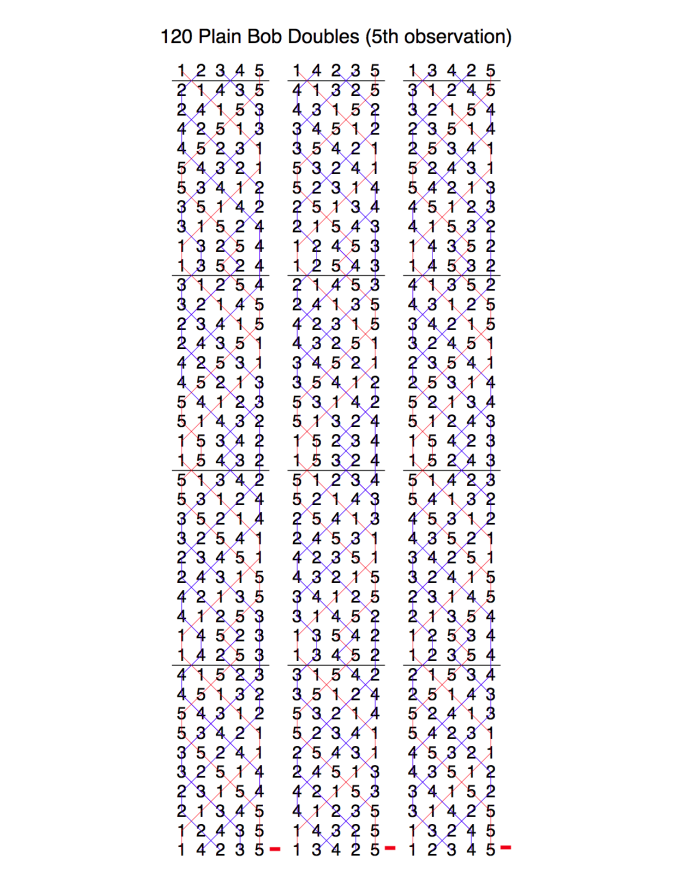

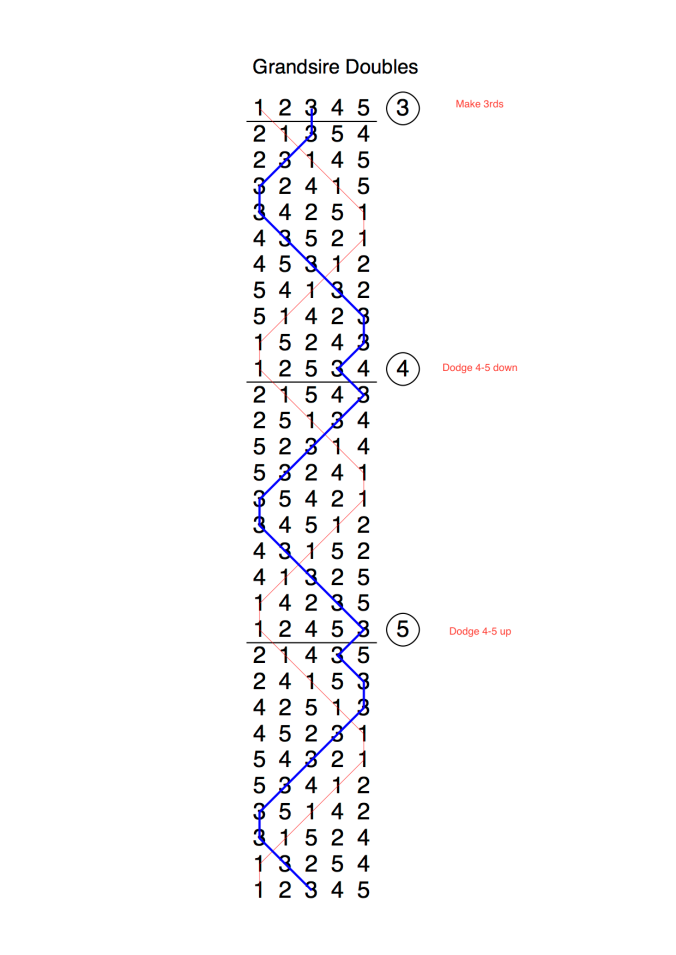

Notice how, at the bob, the 5th makes 3rds just before the treble leads. Notice also that the 5th takes over the role that the 2nd had in the plain course (to plain hunt all the time). The 5th becomes the new hunt bell until the next bob, and the 2nd takes over from it as a working bell.

Notice how, at the bob, the 5th makes 3rds just before the treble leads. Notice also that the 5th takes over the role that the 2nd had in the plain course (to plain hunt all the time). The 5th becomes the new hunt bell until the next bob, and the 2nd takes over from it as a working bell.